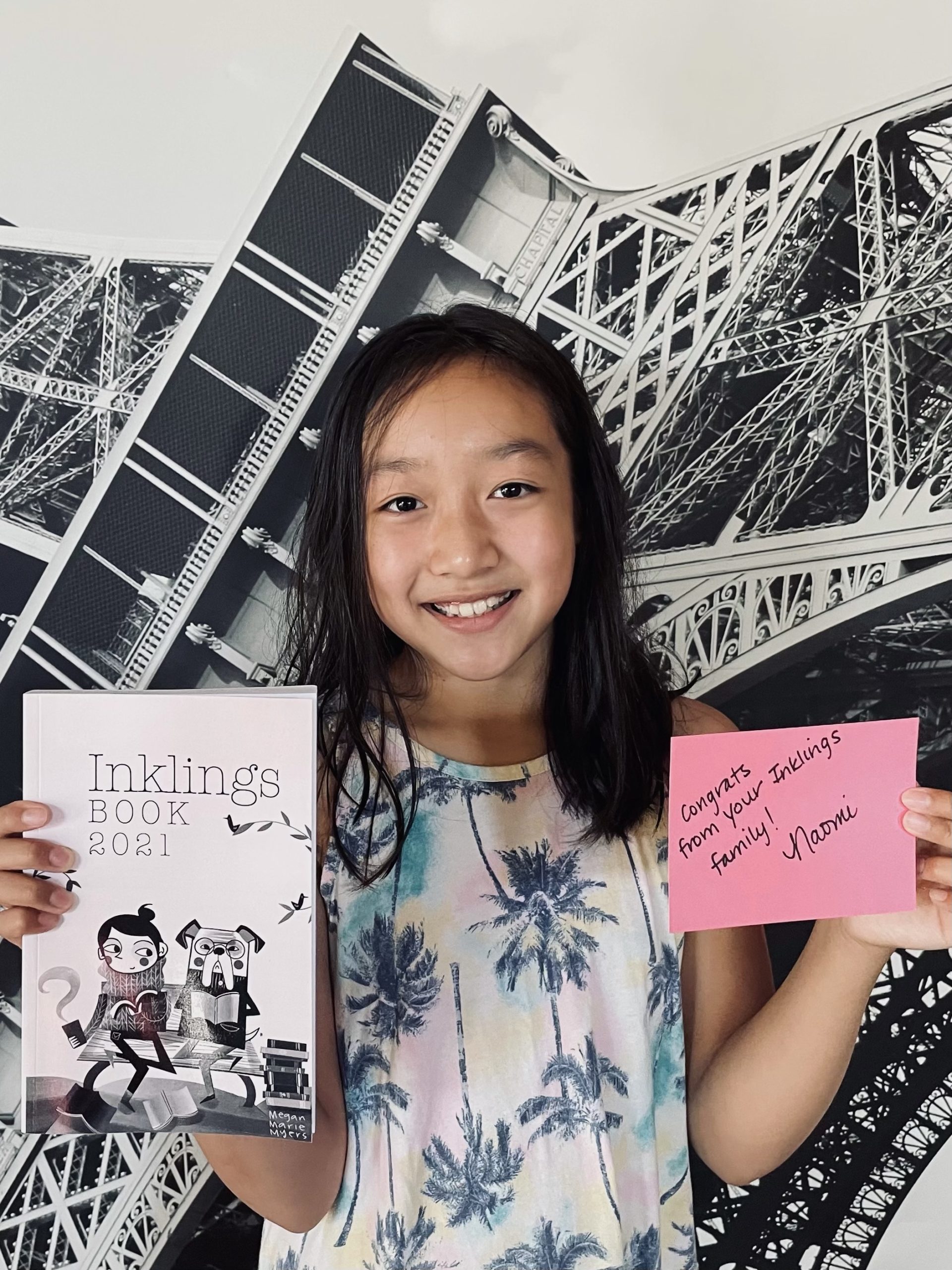

Today we are featuring Inklings Book Contest 2022 finalist Lucia Xiao. Lucia finished 8th grade this past school year and wrote a story called “A Lesson Through Words.” Lucia has remarked that she enjoys the relationship between the teacher and the main character because “they come to understand each other with the similarity of both immigrating to America and leaving their home country in order to begin a better life.” Enjoy!

A LESSON THROUGH WORDS

By Lucia Xiao

This story takes place during the 1900’s. At this time, Russia was viewed as an impoverished country with a growing peasant population and a vast minority of poor industrial workers. Many immigrants from Russia came to America with hope of starting a better life with their family.

When I first came to America with my family, I didn’t know what to expect. The smell of foreign engines that chastened the road, the crinkling of newspaper that danced with the wind. Everywhere I went, strange eyes stared back at me as if they were vowing to dig down the deepest secrets in my soul. I felt afraid. I felt different. America wasn’t like the home I was used to.

The moment I stepped foot onto new land, a strange sensation similar to the humming of the ocean before a big wave came flew through my veins. I could feel the world pushing in on me, but at the same time, the box that had always been enclosing around my soul felt expanded somehow.

It had started with the boat. That oddly giant shape floating on the surface of the blue sea was anchored to the harbor. It could have been so free, that boat. But instead, it was stuck at shore with nowhere to go.

A sailor was waving to people down below. I could faintly make out what he was saying; “come hop aboard this ship to get the ride of a lifetime!” If only he knew how hard it was to come to America from the other side of the world. If only he realized the journey I had taken, would he change those words to, “come hop aboard this ship to expand your vision of the world!”

Another spectacle I had seen in America was the newspaper boy. There were many of them, actually. With each corner I turned, a young man around my age would hold out his bag full of papers and beckon people to come take a look. Sometimes his persistence worked, sometimes it didn’t. To be nice, I once took the newspaper. The boy grinned at me and tipped me with his cap. For some reason, that made me blush. I didn’t know why, for I had these similar experiences back in Russia where my male classmates would strike up conversations with me. In America, however, it felt different. This sure was an interesting place.

Bakery shops and dining areas were everywhere. Out in the open or hidden behind some street lamp, you could always find a place to rest. I could smell the warmth of the coffee from distances away. I could breathe in the love that couples devoted to each other as they sat across a small, round table.

Cats and dogs roamed the fountains. Pigeons scattered below and above me, trying to nag the crumbs that hurried workers spilled. Young kids cried in the morning as concerned mothers tried to calm them down.

I wonder what else America would offer me. People said there were opportunities here. They said that if one worked hard enough, even as an immigrant, they could make great fortunes.

My mother, along with my brother and I, moved to America from the far country of Russia. We came here due to the fact that many of my Ma’s friends wrote ecstatic letters about finding better working places, housing and food in this strange country compared to the lack of necessities we were given back home. Since my family came from the countryside, farming was tough as the droughts raved on. The government wasn’t doing much to help. As the days forged on, widespread poverty and starvation were hitting us, despite the many efforts that Ma made to conceal the truth.

“We’re coming to America to start a better life,” Ma had whispered in my ear. I remember that Alpen had been sleeping in the bed above our farming cottage, and since I was older, I guess that it was expected I was to understand compared to my nine-year-old brother.

“Olga, my dear, you are to go to school there. My friends from America have said the education given to American children cannot be compared to.”

“But Ma,” I had said, fearing meeting people in a new place. “I like my school here. I don’t want to move. I’m doing just fine, I have friends. The drought will pass soon and we will once again be able to live.”

At that time, I can only recall the sad smile on my mother’s lips as she tucked me into bed. I didn’t know the decision was already made that we were to travel to America. If I had, I wouldn’t have been so stubborn in staying in Russia. I would have paid heed to my mother’s words as we embarked on a journey that felt like it took eternity to come to an end. But even as the ships came to dock and I first set foot upon entering a new land, my path to freedom had just started.

School. I didn’t want to go. I didn’t want to meet new people, but what choice did I have? American kids, did they accept people who were different from them? Would I have to leave my past behind to blend in with a new group of people? Would I become a totally different person?

Mother had told me not to worry. She had said that my heart was stronger than any of the words any classmate or teacher would say to be.

“Remember who you are, Olga. You are strong, you came this far. Don’t let anyone put you down. You are my brave, daring sparrow flying straight into the clouds.”

Ma’s words stayed in my ears as I had entered the big brown door at the entrance of my new school. The gray, rocky, building was bigger than I could have imagined. It made my life back home in Russia seem so trivial. The students rising above the steps beside me, the sound of birds chirping in the distance. Was I really ready for a new change?

Keep pushing, Olga. You are brave.

These memories were like fire to me. They were the fuel that burnt the sapphire gem at the tip of night. They lit my world with starlight within a strange, incomprehensible world.

Ma’s words were what kept me going as I entered the big, stone building and made my way in front of a small, wooden door. As I gathered up all my courage to open up the door, I

could feel the heat of dawn as unfamiliar gazes rested upon me. A young woman, someone around my mother’s age, quickly put down a felt book and ushered me in.

“I am Ms. Zoraya,” she said, smiling at me. Her hand was warm as she led me across the wooden floor. “Olga, am I right? Pleased to meet you.”

Before I could respond, my new teacher turned to a small group of children. There were around sixteen students sitting gracefully at their desks with their hands clasped tightly in front of them with their notebooks comfortably at their side.

“Class,” Ms. Zoraya announced, her voice high but strangely sweet, like nectar on a flower. “This is your new classmate I was talking about, Olga. She will be joining us today from Russia. Please try to make her feel as comfortable as possible, for this is a welcoming place for all individuals.”

She turned to me. “Olga, is there anything you would like to say about yourself?”

The heat of my classmates’ gazes bore down on me. I was unfamiliar with the new surrounding of dusty, white chalk and the smell of day’s work. It was as if all American kids were focused on intent studying, and studying only.

“I am from Astrakhan,” I finally echoed out, hoping my accent did not sound as thick as it usually did. “My family moved here to start a new life.” A pause. “I am looking forward to knowing all of you guys.”

I turned to Ms. Zoraya, and luckily, she got the signal that I had nothing more to say.

“Thank you, Olga,” my teacher said with that same smile that greeted me at the door. She then beckoned at an empty desk. “You may take a seat in the third row beside that windowsill.”

As I quietly headed toward my desk, it was then when we began class. Most of the stuff taught to us, surprisingly, I had learned back home in Russia. Whether it was math equations or literature, I didn’t have a hard time adjusting. Only in learning grammar did I have a hard time managing. The strange concepts of English words were foreign to my tongue. The way that the sentences were combined in this strange, American language was so different from how my friends and I back in Russia would speak.

What did Ms. Zoraya expect from me? After all, I wasn’t from America. I wasn’t born with English as my first language.

I remember this one day where each of my classmates and I were supposed to go up to the chalkboard when we were called on and label the specific functions of words in a sentence. Getting up in front of the class was never my strength, but I was usually at figuring out the answer when it came to literature, math or science. But with grammar, I was stuck.

“No, Olga,” Ms. Zoraya, frowning, had said to me for the fourth time since I was called up. “I told you, the adjective goes before the noun. And yes, the word you labeled to be an adverb is actually a gerund.”

My cheeks had started to burn as I gripped the chalk tighter in between my fingers.

“I’m sorry,” I muttered, unable to look at my teacher. “I don’t understand.”

Ms. Zoraya sighed. “It’s okay, Olga. I know that this must be hard for you. We can try again next time. Next person, up the board.”

I almost wanted to laugh. If she knew that it was hard for me, why did she make me do it in front of the whole class? I didn’t understand. It made me look worse in front of my classmates.

It was a constant reminder that I was not an American. I was an immigrant who came here from a foreign country. I was forever different.

“Great job, Sama!” The tone of my teacher’s voice as she complimented my classmate sounded far more satisfied than when she talked to me. I felt like burying my head in my hands.

The clock seemed to go on forever as the seconds ticked by, and I longed for the moment that school would be over and I could go back to a place where I could speak Russian comfortably.

Riing.

“Class is over for today. You all are dismissed, and remember, please do your homework worksheet and bring it in tomorrow for review. We will be going over phrases and clauses!”

I heard a shuffle of footsteps as I heard my classmates laughing and talking excitedly together. It had been a Friday afternoon, so most likely people were making plans and going out together. But all I wanted to do was collapse in my bed back with my family and forget about the dreadful day. We had spent more than enough time studying for grammar than I ever needed to know.

Before I could even make it one step out the door, I had heard Ms. Zoraya calling out to me in that pitched voice of hers. My blood turned cold.

Please don’t let her say what I think she is going to say.

“Olga, do you have a moment? I would like to spend some extra time with you reviewing today’s lesson. You are a very bright student and I am sure a few extra minutes on this topic will keep you up and going along with your classmates in no time.”

I swallowed, very much knowing that I needed no more time in this hot and stuffy classroom. I felt as if the walls were closing in on me and forcing my head to transfigure out a way around a black maze full of vengeance.

But instead of objecting, I turned around and said, “Of course, that is no problem.”

Ms. Zoraya smiled, but it seemed more relieved than the ones she would usually give me on a daily basis, on the note that we were not in grammar class. Had she been expecting me to nod my head and comply?

“That’s Great, Olga. Please take this seat next to me and make yourself comfortable. We won’t be here for long.”

I smiled obediently as my heart beat faster with one look at the thick, white stacks of paper on my teacher’s desk. There was nothing more I wanted to do than crawl into a hole and surround myself with walls to keep me away from the classroom.

“Alright, so we’ll begin with demonstrative pronouns and subject complements. In a sentence, you can always tell that a word is signaling to another noun in a manner of speech. We call this…”

Mr. Zoraya marking and circling words, sentences, even letters on my paper. I myself, nodding my head in understanding, brows furrowed in concentration. This was how most of my lessons with my teacher went. If I were to be completely honest, getting personal attention was not as bad as I thought. Maybe it was just the rest of the class staring at me that made me nervous whenever I got up to the board. I noticed that with Ms. Zoraya, alone, grammar seemed just a little bit easier.

“…and this is an indefinite pronoun while I believe that the one you underlined is a demonstrative pronoun.”

The pen in my hand seemed much lighter as I labeled the sentences that Ms. Zoraya had written on the chalkboard. When I finished the very last one, my heart was thumping widely as if I had just run a mile race. Tiny droplets of sweat beaded my forehead.

“Amazing job, Olga! I knew that a little extra help wouldn’t be too bad.”

I didn’t know what to say at first. To be honest, I always knew that my teacher wanted the best for me, I just hadn’t wanted to admit that I was different from my classmates. Maybe the desire of wanting to fit in had been so strong that my instincts overtook me and I ran away from my weaknesses. Ma had always told me not to do that, so maybe it really was time for me to finally stand up and understand myself and really live in America. School, my classmates and my teacher all made me realize that my horizon of the world had just begun to expand.

“Olga?”

Ms. Zoraya’s soft voice startled me, and I realized that I must have been quiet for too long.

“I’m okay,” I said, standing up straight. “This lesson was very helpful, thank you.”

My teacher did not respond for a moment, making me think I said something wrong. But just when I was about to ask to be excused, the next few words coming out of Ms. Zoraya’s mouth were not what I was expecting.

“You know, Olga, I’m an immigrant too.”

I dropped the chalk I was holding. It broke into two pieces on the floor. “Oh,” was all I could say. This was quite a surprise. Ms. Zoraya’s speech was perfect. She knew every detail about American history. There was no accent that tinted her words. How could she not be from here?

“I came here with my family at age eighteen.” My teacher’s voice was soft, as if she was reminiscing about her past. “There was a war in Germany. Food was scarce. The government was falling. The home I had once known was gone.”

“I’m sorry,” I whispered. There wasn’t anything I could say to relate. War, after all, I heard, was a terrible experience.

“I’m sure this is similar to the reason you came here as well, Olga, but my father wanted me to become a teacher in America. He said that I could earn a good living and be happy with lending knowledge to others.” Ms. Zoraya tilted her head at the window as a single sparrow soared above the clouds, its wings tinted with the golden specks of the sun. “I was looked down upon. My colleagues said that someone like me who came from Germany would never truly be America. Back then, my home country and America were in a bad relationship with each other. I couldn’t make anything better. I couldn’t change anyone’s mind. All I could do was work hard, prove everyone wrong. I had to stand up for myself and create a future that could possibly turn around my perspective.”

A pause.

“Now look where I am.” Ms. Zoraya turned to me, smiling that warm smile of hers. “I have a happy life, I even have children.”

I was very well aware that my teacher must only be comfortable about sharing her past because I was an immigrant too and we could both relate to each other.

“I am sorry if I made you feel ostracized, Olga. I know that it must have been hard. It took me a while to learn the English language as well. But never give up, Olga. Even if you feel as if you are different, don’t let the world berate you. There will always be hope.”

I gripped the sides of the dress and nodded. “Thank you, truly.”

Ms. Zoraya allowed me to leave the classroom, but throughout my whole walk home, I thought about my teacher’s words. She was right. It was only natural for me to be a little behind my classmate in terms of the English language. And it wasn’t as if I was bad at school. I could become as amazing as my American-born classmates if I put in my best effort. This was why I was here after all. Ma wanted me to start a great life. She knew that there were opportunities here, and I, Olga, would not let her down.

Support the Inklings Book Contest Today!

Your support of the Inklings Book Contest helps us connect with youth writers and provide them with free learning opportunities throughout the contest – as they prepare, as they enter, and as they revise their work as winners and finalists.

Will you support the next generation of writers as they find their voices and make their mark on the world?