Writerly Play Kit 014

Bridging Between Play and Writing Craft

Bridging Between Play and Writing Craft

Play boosts energy and enthusiasm. Games also give educators the opportunity to guide writers through questions that will layer their ideas. In many ways, play can be a rough draft, a place to experiment and explore.

Play brings many benefits, but the bridge between play and application on the page can be tricky to facilitate. How might we help writers harness their creative energy and integrate writing craft with their innovative thoughts?

In this WP Kit, we’ll explore the mindset required for playing and drafting vs. the mindset required for crafting that initial material into our very best work. How can we help our writers bridge between the two for effective and efficient writing?

Aha! Moments through play

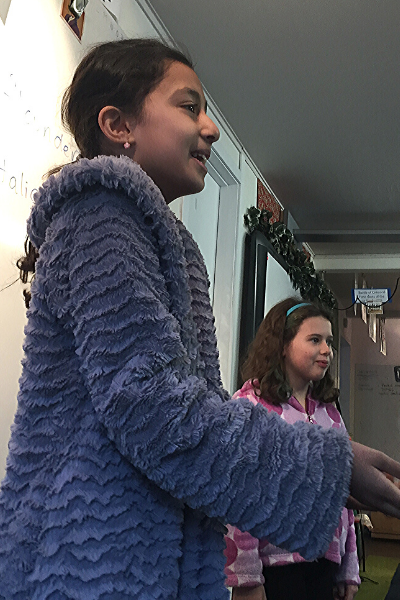

So, for instance, writers might begin by moving around the classroom in a few simple ways. Younger writers are quickly engaged with imaginative prompts, where middle schoolers might prefer moving at different speeds. Once the group has moved past giggles or resistance, and are all collaboratively following prompts, it’s time to add complexity to the game.

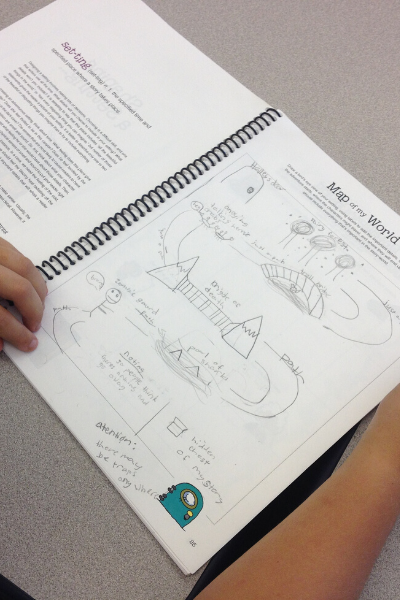

For instance, writers might “Walk As If,” guided by your prompts that support them as they explore ideas, choose one, and then layer it with sensory detail. Or, you might guide them back to a fresh sheet of paper at their desks where they follow your prompts to draw a map. Our goal is to keep writers grounded in their bodies. We want them to top into spontaneous connection-making, rather than judging their ideas from their critical minds.

The deeper into that flow state of play writers can go, the more likely they are to find a truly innovative (and delightful to them) idea. It’s important to remember that learning to play is a key step in the process. Sometimes they can’t have that fantastic experience on day one or three, just like we may not feel like we’re flying on a bicycle on our first or third ride. Each play session builds our stamina, focus, and trust in the process.

crafting our writing

In order to transition writers, I start by thinking about their bodies. If we’re moving around the room, I may coach them into a quieter, calmer type of movement. I may ask them to freeze and close their eyes. Then, I think about their minds. Often ideas are buzzing wildly and they need a chance to let them settle. I often coach writers to take ten more counts to collect any last ideas. Then, I invite them to the carpet area. Once we’ve gathered, I consider their emotion. I might acknowledge their excitement, or assure a group that looks a little worried that we will keep thinking–they don’t have to have all the answers right now.

Then, I model by thinking aloud for them about how I might take an idea from the game and apply it to my writing. I often use templates to capture thinking because the labeled boxes and lines echo the prompts I used while they were playing. Now, in this more quiet, analytical space, they can use the momentum they gained while playing, and make more measured decisions on the page.

I think aloud about a few choices, particularly about those issues that could be stumbling blocks, such as that this scene isn’t about eating, so will I even include those cookies? I might note that my character could be dreaming of cookies while she’s in writing class, but then realize that my character loves writing, so she probably wouldn’t be distracted like that. I don’t have to force every detail into every scene, so maybe for now, I’ll focus on that friend that moved away. Maybe my character will write about a time they carved pumpkins together, and while she writes, think about how much she misses her friend.

Eventually, I help my writers become aware of the transition from play to craft, but in the beginning, I create that experience for them step-by-step. As they are able to become partners in that process, they gain even more benefits from their play sessions, and can dive even more deeply into their writing craft.

–Stuart Brown, Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul

What’s Up At SYI this Month?

STUDENT WRITING CHALLENGE

Scene vs. summary

Kalyn says, “One of my favorite exercises is to experiment with scene versus summary. I write a scene and then attempt to summarize it. It helps me figure out what’s important info and what needs to be seen versus told.”

Try this: First, write a scene where two characters attempt to solve a problem. What if, by the end of the scene, everything is worse than it was to begin?

Next, write a summary of your scene in two-three sentences.

Then, rewrite the scene. Focus on the elements of the scene that are clearly most important, amplifying the humor, chaos, or other high emotions of those elements.

Aim for between 350 and 1000 words. Have your students submit their responses at younginklings.org/submit and they might be published on our website!

INK SPLAT

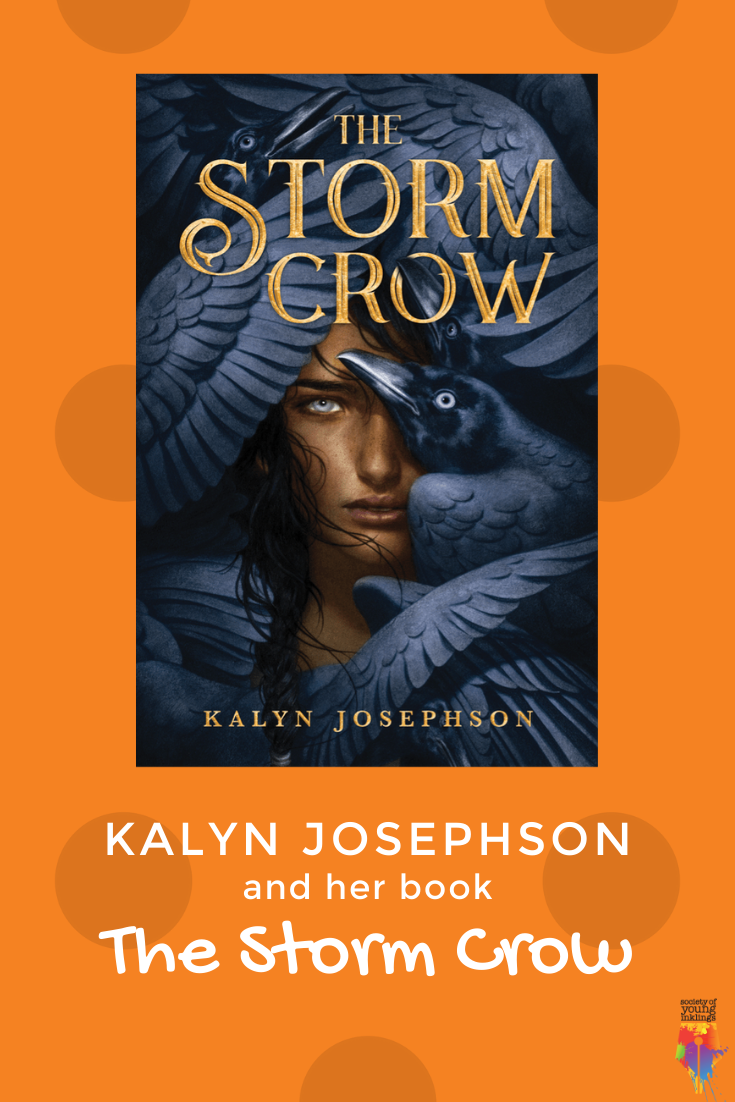

Kalyn Josephson

This month, we talk to author Kalyn Josephson about her novel, The Storm Crow. She talks to us about the road to publishing her debut novel and the complexities of portraying a character struggling with depression in a fantasy novel.

“I wrote and queried 3 other books before I finally signed with a literary agent for The Storm Crow. I also did a number of revision rounds before signing with my agent and then again with my editor once the book sold. Suffice to say, it’s been a long, hard road!”

INKLINGS CELEBRATE

Join us for Summer Camp!

We’re inviting passionate young writers to join us on Zoom for writerly summer camp experiences. Each camp will include skill-building activities, time for drafting, and collaboration with peers.

Bring active learning into your writing classroom.

Writerly Play offers an untraditional doorway into the writing process. Through a variety of games and activities, your writers will take action and tackle various genres of writing. Writerly Play utilizes games to facilitate creative and critical thinking at every stage of the process, from idea generation to idea development, to drafting and revision, and even through the sharing of work.

Try out Writerly Play in your classroom with our series of videos designed specifically for educators. Use one video to spark a story idea, try a poetry activity, or use the full series to support a creative writing unit.